History Behind the Story #9: The Navy Before the Civil War

Spoiler alert! If you have read Southern Rain, you know that my historical male lead, John Thomas, attended the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland (which is how he met Shannon’s brother, and, ultimately, Shannon). From there, he goes on to enter the Navy and ultimately is a Captain before he heads off to war. Becoming a Captain seems like a bit of lightning-rise in rank, but considering the state of the Navy on the cusp of the Civil War, it wasn’t really. People with John Thomas’s education and a dab of experience were in high demand because if there was one word to describe the Navy when the Southern states began seceding, it was unprepared.

In 1843, the Navy was on the rise, technologically speaking. America rolled out the first propeller-driven steam warship in the world, the USS Princeton, but during a public relations cruise, one of its guns exploded, killing the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Navy, and that successfully halted interest in Naval expansion.

Further jinxing the Navy, its officer rankings seemed almost designed to stunt its prestige. The highest rank one could obtain at the outbreak of war was that of Captain, meaning that in any dealings with the army, Generals would always feel like they outranked Naval Captains and had the final say. It wasn’t until 1862 that the ranks of Admiral, Vice Admiral, Rear Admiral, and Commodore would exist in the U.S. Navy.

In addition, America’s geography did not seem to leave it much in need of a Navy. In consequence, there were fewer than 90 ships owned by the Navy at the start of the Civil War, and only 42 of those 90 were ready for action. Of those 42, most of them were overseas on a tour from Brazil to China. As a result, Lincoln had only 12 ships at his disposal at the outbreak of war.

Technology lagged, too. It wasn’t until 1854 that America built its last ship that would be propelled by wind (sailing) instead of steam – yikes! The government then started building steam frigates and naming them for American rivers. These new frigates still had sailing capabilities, meaning they weren’t exactly a giant leap towards modernity. They averaged only about 5 or 6 knots under steam. Also, they were huge, too big to pull into most American ports. This led to the production of “screw sloops,” which weren’t quite so deep (one would even be able to traverse the Mississippi River during the assault on Vicksburg). And finally, a new class of warships that was entirely steam-propelled would make up the third generation of steamers, and they would all be named after Indian tribes.

These new warships were revolutionary because they carried modern guns capable of immense damage. Explosive shells from ships were the Civil War’s equivalent of dropping bombs. The guns were also rifled, which meant the projectiles emanating from them had a spin, meaning in turn that they could hold their trajectory over longer distances. This made it possible during the Civil War for combat range to be 20 times what it had been in previous wars.

And so, while there had been some innovation, there was surprisingly little effort put into giving the U.S. a robust Navy.

Southerners were at the forefront of innovation. They hoped to extend American influence (and slavery) into the Caribbean and Central America and had been Naval-minded for longer than other regions. However, the Confederacy had absolutely no navy at all before the Civil War. They built their entire Navy from scratch with remarkable innovation and industry at the outbreak of war.

A few ships were seized by local authorities in the South as states seceded. While Confederate authorities urged Naval officers who were Southern-born to bring their supplies and ships with them when they returned home after secession, none of them did, handing their men and materiel over to federal authorities before going South (like John Thomas’s friend Shalto Hughes does in Southern Rain).

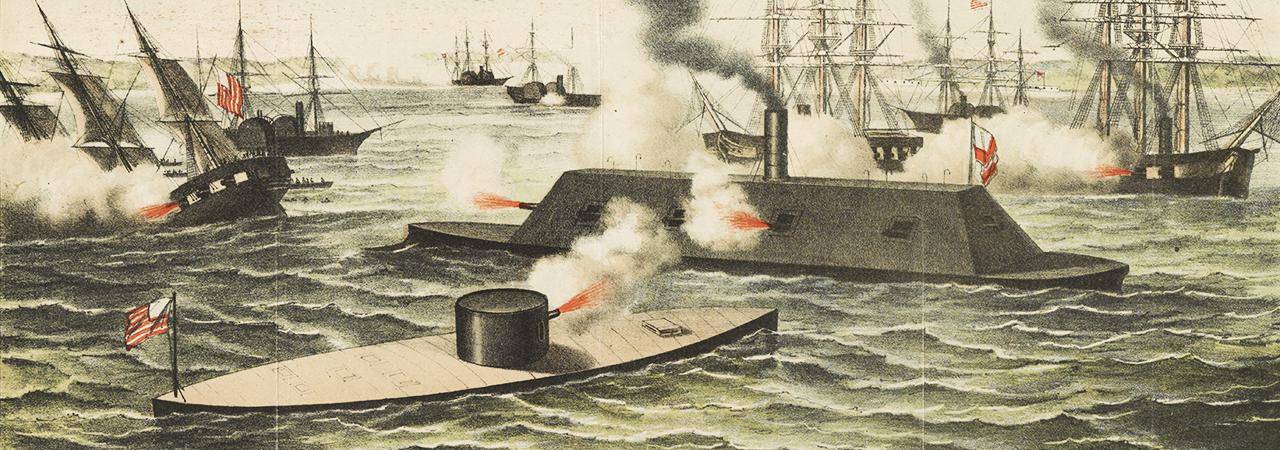

Lots of people know that in the first naval battle of the war, the South’s ironclad absolutely destroyed the North’s ships. If you’re like me, though, you never questioned how the South got its hands on an ironclad so early in the war. Ironclads were just being invented right at the outbreak of the war. These were the mother of all naval vessels and ultimately became the preferred vessel for almost every expedition. Picture the effect a spinning, flaming shell would have on a wooden ship (explosion) and then picture the same shell thunking off of iron into the water harmlessly, and you’ll get the idea. But how did the South get an ironclad into its possession?

I’m going to quote Craig Symonds from his book, The Civil War at Sea. “When Virginia seceded in April of 1861, the steam frigate Merrimack was in the Gosport Navy Yard near Norfolk for an overhaul of her weak and unreliable engines.” The Secretary of the Navy ordered the commander to get it out of the yard, but the Commander broke nervous at the sight of a mob and sank it to keep it from falling into Confederate hands. “[The men] set fire to the masts…, still visible above the water…”

Okay, so if you’re like me, you don’t see a future for the Merrimack here. However, Stephen Mallory, the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, ordered that, “The possession of an iron-armored ship…[was] a matter of the first necessity.” Now, Southerners, from my experience, don’t waste anything, and the Merrimack had already been hauled out of the river and salvaged. Mallory began to wonder if this new-fangled idea, an iron casemate, might not be possible to put on this conveniently left steam-powered ship the Confederacy had acquired. So they literally built armored casemate on top of the Merrimack.[1] The Virginia (the Merrimack’s new name) dealt a huge wound to the Union Navy and morale at Hampton Roads in March, 1862. And that would alter naval warfare forever. “The London Times wrote: ‘Before the duel off Hampton Roads, the Royal Navy had 149 first-class warships. After the battle, it has just two.’ Wooden ships were now obsolete.”[2] The Union got down to business, building 84 ironclads during the war, and, ultimately, it would be the more successful Naval force.

The Confederacy at first intended to rely on fortifications, but the new ship technology had made ships a winner against forts almost every time. Since the Confederacy didn’t have the resources to build a huge navy, it was always at a disadvantage, and (this is just me personally) I don’t think enough emphasis has been placed on the U.S. Navy’s ultimate contribution to victory. Historians are always careful to caveat those contributions with, “Of course, it was primarily a land war, so the Navy couldn’t really be the reason the Union won.” And that may be true, but I often wonder what the Civil War would have looked like had the Union not been able to bring its Navy up to speed. What would Vicksburg have looked like, or the ultimate fall of Charleston? What if the U.S. Navy hadn’t formed such a successful blockade of the Southern coasts, and the South had been able to resupply from Europe? I think the Navy played an exceptionally vital role in the Civil War and imagine that the war would have been prolonged for years without its ultimate successes.

If you would like to read more about the Naval War, there are several books out there. One which was surprisingly helpful was Grant, by Ron Chernow. I say “surprisingly” because Grant was an Army man, of course. But Chernow’s research shows how vital Grant felt the Navy to be in ultimately winning the war.

Sources:

Symonds, Craig L., The Civil War at Sea (Oxford University Press, 2009).

“The Naval War of the Civil War,” https://www.historyonthenet.com/civil-war-the-naval-war.

Image Credit: https://www.historyonthenet.com/civil-war-the-naval-war.

[1] They were literally ripping up rail roads to get enough iron for the Tredegar Iron Works to melt down.

[2] https://www.historyonthenet.com/civil-war-the-naval-war.

Charleston during the Civil War: